Studying the floor in the psychiatrist’s room one Summer’s day, I felt simultaneously ashamed and relieved. I was fifteen when I was diagnosed with ADHD. Thanking my psychiatrist, I decided to keep this a secret and managed my emotions by over exerting myself where I felt most comfortable; being a responsible sibling (and later parent), championing creativity and self-expression in my classroom and seeking meaningful connection with friends and strangers.

Having ADHD is a little bit like having multiple tabs open in your mind; in conversation we jump from topic to topic; our physical space is cluttered; we are restless in nature and in thought. We thirst for answers and crave novelty and meaning. We are utterly loyal and pour our hearts completely and willingly into what we love, whether that’s a person or a creative endeavour. But loving this fiercely makes you uniquely vulnerable. Keeping a trustworthy, supportive inner circle leads us back to safety.

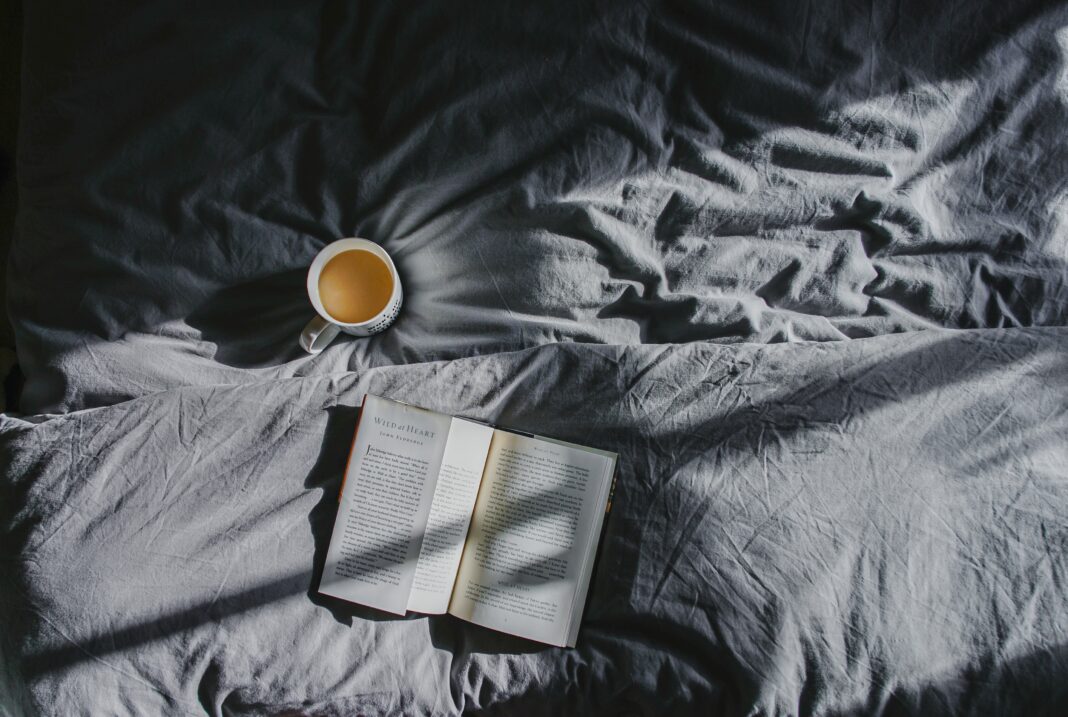

Where words and company fail, my home becomes my sanctuary; the coolness of clean sheets hitting my skin as I sink into a new read, lashings of rain playing the rhythm to my quiet Sunday. A homemade dinner for two might not include quail eggs and chia seeds, but there’s something exquisitely intimate about sharing the responsibility of cooking over laughter and whispers, or obsessing over which pair of earrings say coy but fun. Domesticity can sometimes be given a bad name but the couples (and individuals) I often observe as content are comfortable finding novelty in the mundane. A dance on the kitchen floor as your child sleeps, play wrestling and love notes hidden in each other’s pockets. There is no end to how we can express longing and warmth in a safe and secure relationship.

As much as I dislike routine it has helped my growth to invite it in. Seemingly insignificant, overstated factors like adequate sleep, disconnecting at specific times, journaling following a fallout, a nature walk to recharge social batteries and reading before bedtime help me regulate my thought patterns. These routine checks give you a sense of accomplishment, something I learned the importance of in my teacher training. The more we feel able to complete a task the more likely we are to attempt it. The first step to feeling better is remembering that you can and will be better.

Unlike depression and anxiety, ADHD is still largely misunderstood and often brushed aside as too new age to be taken seriously. I work with children who have ADHD. As a teacher, I worry my children will feel misunderstood or insignificant as I have in my own battle. When my fears get the better of me, I think back to how this condition has added value and richness in my life; a commitment to protect the vulnerable because I have once felt that way, a resilience in spirit and an appreciation of creativity; the meeting place of minds and stories where we reclaim that we are not reduced by what happens to us.

That Summer’s day in my psychiatrist’s office I remember being given a piece of paper detailing all the famous and interesting people who had left their mark on the world in spite of their ADHD. I remember Da Vinci. I remember hiding the paper under my pillow. I remember the few people I trusted the information with. My best friend Aalia, my guilt-ridden mother and a junior doctor aspiring to be a psychiatrist because of his own ADHD. Meeting Ali was like looking at a male version of myself. We both took it in turns to be late and I found it strangely comforting to have another person share my flaws. It was also the first time I forgave myself for having the condition.

When I strip my feelings of shame and guilt, I feel a deep-seated longing for safety and normality, a frustration and impatience with myself that my mind is cluttered. To the outside world, this goes by undetected with a smile and my playing the role of helpful human. Being committed to self-compassion has meant forgiving myself for all of the above. On the other side of self-compassion is a freedom to let yourself be misunderstood, a freedom to forgive your own mistakes and self soothe with the same high regard as you would someone you admire.

On my darkest days, I remember questioning God why I never received any kind of reward for the difficulties I had faced. I felt hurt that the most important men in my life had been separated from me, angry that my child would have an imperfect upbringing, detached from my loved ones because my emotions were too heavy to disclose. Now when I’m tempted to go down that path again, I feel an overwhelming gratitude that I have been given far more than I ever asked for and far more than I ever imagined I deserved; a loving husband, a happy child, a mother that exudes wisdom and a quiet strength. ADHD cannot take these away.

As I type this in panic-stricken Britain during COVID-19, now more than ever, is an opportune time to hold up everything to the light and question how and what it is contributing to our joy and mental wellness. What all storms have in common, however constricting our circumstances, is that they all pass and as they lift we emerge wiser, more trusting of our own ability to overcome and thrive and hopeful in the knowledge that the best is yet to come.