The creators

London-born Akram Khan is of Bangledeshi heritage, and a choreographer known for injecting his South Asian roots and contemporary dance into his work. At the ripe age of seven years old, Akram began dancing and trained in the classical South Asian dance form of Kathak, one of the eight major forms of Indian classical dance. Kathak is traditionally attributed to the travelling bards in ancient northern India known as storytellers. Khan’s work is recognised as being profoundly moving, in which his intelligently crafted storytelling is effortlessly intimate and epic. Described by the Financial Times as an artist “who speaks tremendously of tremendous things”. One of the highlights of his career was the creation of a section of the London 2012 Olympic Games Opening Ceremony that was received with unanimous acclaim.

The Academy Award, BAFTA and Grammy winning director Asif Kapadia can be explained as nothing short of marvellously unpredictable. His first feature film, The Warrior (2001), which stars the late Irfan Khan, was shot in the Himalayas and the deserts of Rajasthan. The film won two BAFTA awards: the Alexander Korda Award for the outstanding British Film of the Year 2003 and The Carl Foreman Award for Special Achievement by a Director in their First Feature. But perhaps Asif is best known for his acclaimed trilogy of documentary films Amy, Senna and Diedo Maradona. Amy, a documentary which captures the life of singer Amy Winehouse, has now become the most successful British documentary of all time, winning the Academy Award, BAFTA award and a Grammy award for Best Documentary. When thinking about what Asif Kapadia may have planned next, we can only think that the sky is the limit.

So, what happens when a director, who has until now never been to see a ballet, meets a choreographer who has never ventured towards working on his own feature film? Well, you get Creature of course.

Creature is a ballet meets feature film fusing the two form of arts to portray a message of exploitation, harassment, the hierarchical roles society places us in and dictatorship, all while following a story of compassion and love. An incredibly intense yet enticing production where the viewer is left mesmerised in a hypnotic state as the play unfolds. Its gothic theme leaves us believing this is the greatest oxymoron indeed: a disturbingly beautiful film. There was not a huge budget for the movie nor was their much time to create this production but despite all this the end result is impeccable.

“You know, it was made with very little budget very little time. I pulled favours from crew pull favours from people who were just like, let’s just shoot it, and then we’ll see,” laughs Asif. “There was a window of 10 days when the dancers were available. I thought, we have 10 days, I think we can film a movie. So, we put a crew together quickly. Something like Senna took five years to make and most of my films are like three years in the making from beginning to end. This film we had, with the filming and editing, about two months to complete.”

Creature

The opening scene uses incredible images and clips of Earth, from outer space to close-up landscape clips. The extraordinary clips that the director used to begin this production we later find out were clips from previous work he has done as well as favours pulled in from NASA itself.

“That’s all one location,” Asif explains. “We had 10 days in one location, anything that you see that’s outside of that location, I’ve either borrowed and stolen from my own films. All the arctic stuff is from an old film called ‘Far North’ that I did. And then the arctic fox shot in the beginning, I saw that on Twitter or something! I said ‘let’s see if we can licence that shot of an arctic fox,’ and got some free stuff from NASA of the Northern Lights.”

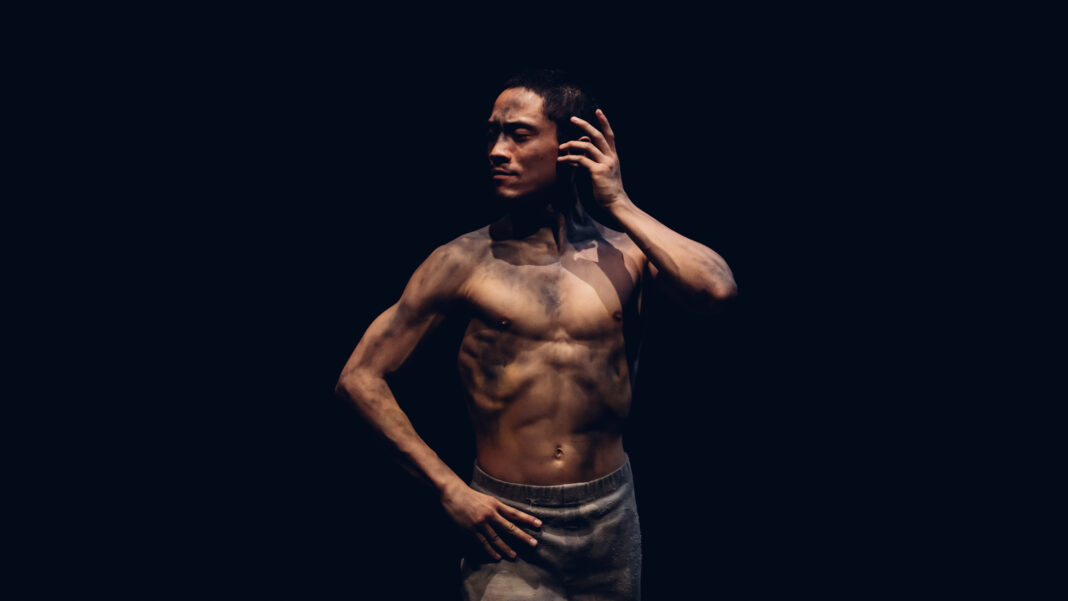

As we meet our nameless protagonist in his opening scene, we are close-up and can feel every precision in his movements down to the fingertips. Something not normally achievable in a film production. In fact, we feel so close to the characters you can almost feel their breath. This intensely up-close and personal experience affords such an incredible new dynamic to the ballet experience, as Asif weaves us into this larger-than-life play, allowing us this almost immersive experience where you have access to all the crevasse of the stage and nothing is out of bounds.

The scene of the story seems to be based in an experimental arctic site where Creature is tested to his limits and somehow, despite the awful experimentation and pushing of his limits, he shows absolute resilience. The beginning scene also introduces Creature’s love obsession, Marie the cleaner. He is besotted by her and tries to win her affection. Marie shows a lot of resistance despite it being clear that she feels the same. Her fear of falling out of line from her role pushes her away from Creature. However, Creature is not the only one after Marie’s attention – his competition is none other than The Major.

The villain

The unscrupulous Major who portrays exploitation and dictatorship is the distasteful villain in the film. He uses brutal force and aggression to feed his selfish desires and can be seen harassing Marie at any chance he gets. His presence on stage omits fear and it becomes very clear that this dictator demands control. He uses manipulation when trying to lure Marie. She is extremely uncomfortable in his presence and can be seen trying to gently reject his advancements. However, The Major is not one to take no for an answer and clearly feels entitled to take what he desires. The Major has no regard of doing this secretively. In fact, all his interactions with Marie are in public amongst the eyes of obedient staff. No one challenges The Major, though they try their best to save Marie by ushering her to safety discretely. Creature is the only one willing to stand up against him and is not afraid to do what’s right. His courage and bravery infuriate the Major who banishes him to the cold arctic once more.

”It’s visuals, it’s performance and it’s music on a big screen – you don’t need words, it’s not about the words,” Asif expresses. “For me, there’s a story and not everyone might get the same story that I get. Some people think it’s about colonialism or authoritarian regimes. Someone saw it and said ‘that guy’s like Harvey Weinstein, when he points up to the sky that ‘I’m gonna give you an Oscar if you do what I say,’’ and so that idea of power is really what I think Akram was talking about, how people get abused on the bottom of the rung. People come, they use you and abuse you, and bugger off.

“I think Akram was trying to do something on the kind of ‘Me Too’ period and actually, I think even the English National Ballet has got some story that had come out about someone who ran it and who was abusing dancers. So there’s a story of power, now the challenge of that is by showing it, you’re kind of showing a woman being hassled by a man. But I think that was also always in the theme that he wanted to deal with, to deal with these kinds of powerful men taking advantage of people like Creature but also of a woman.”

Leaving the theatre, I felt a sense of awakening from the evil corruption we are surrounded by. The strong sense of self-worth and how both from the mind and soul we are creatures that can be pushed to the brink of extinction, to breaking point, far pass our human limits, yet we persevere – we fight, we challenge, and we conquer.

If like me, you love the world of art in all its forms and the messages conveyed by the artist, then Creature is for you. You don’t have to be an avid theatre-goer or even be familiar with ballet. I am certain that you will feel the intensity of this production and leave with a profound meaning of the greater picture than what is presented before your eyes. It is absolutely worth a watch and I challenge you to walk away not thinking deeper about the society and world that we live in.

Creature is on at HOME in Manchester until March 2nd and the BFI in London until March 6th. The original stage production is on at Sadler’s Wells from March 23–April 1.