EDITOR’S NOTE:

This article has been reposted from the Manchester Museum Our Shared Cultural Heritage blog:

https://sharedculturalheritage.wordpress.com/2021/03/31/being-of-mixed-indian-heritage-and-reframing-the-identity-crisis/

As someone with mixed Indian heritage, and growing up in a country outside of the ones my parents were born in, I would say that my family forms the definition of my community. In the Cambridge dictionary, this is described as people living in a particular area, or people who are considered as a unit because of their common interests, social group or nationality. When I reflect on my own “identity crisis” I cannot help thinking about my dad, who shares many identities and belongs to many communities, as a Parsi (Persian Zoroastrian), an Indian, a South African and as of recently, a British citizen.

Britain’s past weighs on our present, and learning about it means a better insight into race and migration. Unpicking my dad’s identities has helped me navigate my own and better understand the complex history behind Britain’s relationship with South Asia.

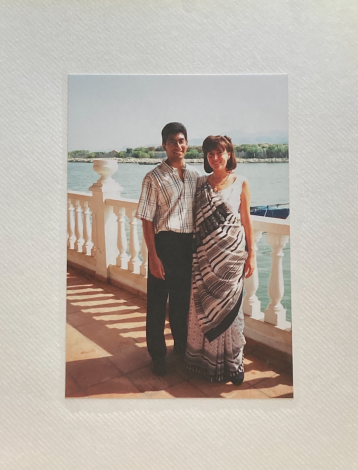

In 1967 my father was born into a Parsi family in Durban, South Africa, with colonialism shaping their lives. My grandparents, after initially emigrating from Mumbai to Mozambique, moved to the coastal city of Durban in South Africa. Because South Africa was under apartheid, a system of institutionalised racial segregation, my grandparents were fortunate in that they could send my father to boarding school in Britain to achieve a better quality of education. At the age of 8, my father was living 8000 miles from home, only visiting his parents during the Christmas holidays, an aspect which has contributed to him feeling removed from his Indian culture and heritage. It was when he was accepted by the University of Nottingham under the British Council Scholarship for South African students that he met my mum, who came to Nottingham on an Erasmus exchange programme from Spain.

Until recently, my experience of being mixed has been overridden by a sense of not feeling comfortable claiming all aspects that I am. One example was when I was applying for this position, as Community Producer intern for the South Asia Gallery at Manchester Museum. Despite being of Indian heritage, I have also been fairly culturally removed from my father’s Parsi community and its culture. I was therefore concerned with my positionality, and whether I was taking up space that would be better suited to someone more in touch with their South Asian heritage. This sense of imposter syndrome is something that I have been subconsciously carrying with me throughout this internship, and it is baggage that I want and need to let go of.

Following the recent podcast with Manchester Museum, which explored the many ways we feel like we belong (or not) as members of the diaspora in Britain, I have been thinking deeply about my responses to some of the questions. In one part of the podcast, Sadia asked me what ethnicity I felt I had a stronger affinity with. The question threw me off completely as it is an aspect of my identity that I feel I am constantly struggling with. Thinking about this question in more detail, I can formulate a clearer and more definitive answer: whilst I currently have a closer cultural connection with my Spanish side, in most cases, I am instantly perceived as Indian due to my appearance. I will never be able to shoehorn myself into only one aspect of my identity – and I am still learning to feel comfortable with that, especially in a society that is constantly leading me to believe I must be having a crisis if I do not belong in one place. In turn, being asked this question has pushed me to face up to these difficult questions that I so often avoid, and do the necessary internal work.

Whilst my sister Leah and I have always had open conversations with our parents about our sense of belonging, it was our grandmas that played the largest role in understanding our heritage. I think when it comes to feeling like you belong, the elderly really do hit different. I was fortunate enough to spend holidays in India, South Africa and Spain and learn more about my ancestry through spending time with them. On my mum’s side, my ‘iaia’ (Valencian for grandma) experienced living under Franco’s regime in Spain. When we would walk down the streets in Cullera (my mum’s home town) we would trace the routes she would walk with her friends and she would recount the failed attempts of men that would frequently lean out their windows and try and serenade them with guitars (can it get more Spanish?). My grandma on my dad’s side was an activist campaigning in South Africa’s fight against apartheid and one of the first Indian doctors in South Africa to be in a managerial position in a hospital – her strength was something I most admire. They have both instilled me with values and memories I will keep forever. My heart goes out to grandparents and the elderly everywhere, I think they can have such a big role in teaching us what we will never learn at school.

I wanted to write a piece on the complexities involved in being a person of mixed heritage, but I didn’t want this piece to only emphasise the internal struggles of never quite fitting in anywhere. There are also great strengths that come with being #BothNotHalf which I do want to highlight. As I can only speak of my own experience, I’ve asked my good friend Chaitanya to join me in conversation to hear more about what her mixed Indian heritage means for her, and our different experiences with identity and belonging.

Hannah Rustomjee (21), identifies as Spanish and South African-Indian, Studies Human Geography at the University of Manchester and is a Community Producer Intern at the Manchester Museum.

Scrolling through the Instagram page ‘Mixed Race Faces’ and seeing all of the beautiful people, made up of a myriad of different ethnicities, skin tones, cultures and religions it becomes so clear that there is no one way to be mixed-race. But, where do I fit in? This is a question that I have been consciously (and subconsciously) battling with for some time now. How do people perceive me and how do I perceive myself? In fact, how do these two questions intertwine in a way that influences my identity? Perhaps, there has become an invisible and silent stereotype or standard that we (mixed-raced) people feel like we must live up to in order to be worthy of the title? For example, are we light enough, dark enough, “exotic” enough, caucasian enough? Not only appearances, but also what role do languages play into this; can we speak the language(s) that are intimately connected to our family history? More importantly, at what point are we actually mixed enough to be that certain “percentage”? I believe that these silent stereotypes infiltrate and interfere with our freedom to identify ourselves, and the way that we feel like we belong and fit in somewhere in society. I believe this to be fundamental to the “identity crises” that many mixed-raced people are facing today – or at least, it is for me.

I am both, not “half”, English and Indian – my mum is White-British and my dad is British-Asian. I am always amused that people immediately envision my dad being born and raised in India, with a thick accent. The question is, if my dad wasn’t British Asian, would this make me feel more secure in my mixed-race identity? However, my dad grew up in a house in Ealing, North-London, which was fully packed with Gujarati mums, dads, uncles, aunties, cousins and his little brother. My grandparents are Gujarati but lived in Uganda where they were forced to flee to England by Idi Amin in the 1970s. Following long conversations that I have recently had with my Baa (Grandma) and Bapa (Grandad), I have been told that there is a cultural difference between Gujaratis from East-Africa and those from India. Even this detail has made me reflect on how culturally different people can be even if in some ways they are also culturally the same. Furthermore, this illuminates that there are endless possibilities of mixes and intricacies which define a person’s unique identity – there are many different ways to be mixed race.

My parents are not together and have been separated since I was three. I think this is something that has exacerbated my feeling of otherness as I feel like I never really “fit”. My parents met at college studying acupuncture, and after falling in love my Mum became pregnant with me. They had known each other for three months. From my understanding, my Indian family were uncomfortable with the thought of my dad having a baby with an English woman, this was not understood as the norm and seen as quite controversial within the community that my dad and his family belonged to. Perhaps as migrants, they were trying to navigate a place for themselves within a foreign country. I understand this as the tension between trying to maintain their culture and values whilst simultaneously moulding to another new one. Even when they didn’t ‘mould’, society found a way to make them more palatable. One example is how my grandmother is called Jenny instead of her actual name, Chandrika, at her workplace, despite having the same colleagues for almost 20 years.

After separating, my Mum has married an Englishman and my Dad has married a British-Gujarati woman. Although this was unintentional, it is interesting to consider when exploring ideas of where people feel they best belong and how race can play a role in this. I have one English sister and one Indian sister which is something that I believe, once again, sometimes accentuates my feeling of not belonging – I am light in comparison to my Indian family and darker than my English family. Because of my skin tone, when I meet new people I am immediately labelled as white and I am never perceived as being half-Indian. This has been frustrating at times and has led me to feel insecure and doubt how worthy I am of being called mixed-race. It makes me question whether I am Indian “enough”. For me, being mixed is rooted in this very notion and has dominated the way that I have perceived myself for years. It was only once I met Hannah that I began to feel empowered and like I belong as a mixed-race face.

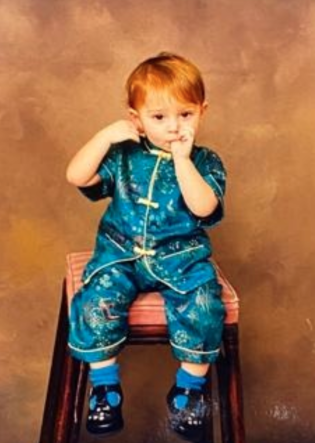

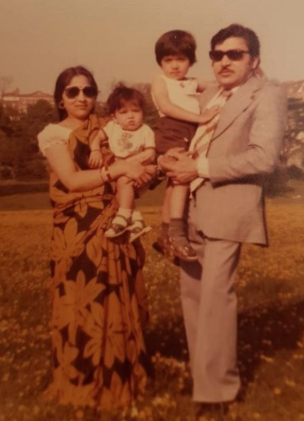

Chaitanya and her parents at a relative’s wedding / Chaitanya, her grandparents, and her mum

This is only a glimpse of mine and my family’s story, but I hope that this is a reminder that you do not have to fall into one of the stereotypes to be mixed-race. Whether you are 10 or 90 percent of something, you should have the freedom to define who you are in terms of where you feel that you best belong. I want you to know that you are enough, you are adequate, you are special and unique, and you and your story fit in right next to mine and Hannah’s.

We would love to hear your story and speak to you. Please reach out. Let’s open up a conversation and make a place for us to feel like we belong.

Chaitanya Makwana, (21). Currently living in Brighton and soon to be an International Development graduate at The University of Sussex. Both English and Indian. More importantly, Hannah’s Erasmus wife.

Recommended Resources

Twitter thread on BAME term: https://twitter.com/adamec87/status/1376526957689573382

Twitter thread on world poetry day about diaspora and language, poem is ‘Homeward’ by Bassey Ikpi – https://twitter.com/muna_abdi_phd/status/1373759905824395265?s=21

Strange Origins Podcast – ‘Identity crisis in mixed race people’ https://open.spotify.com/episode/0gc8mcx7SaCL5dxVDrqxG6?si=qaWLyFiaQIaukl5CwjSyLA

Refinery29 Article – ‘Let’s Stop this Offensive Term from Making a Comeback ‘https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/half-caste-offensive-term